History of the #Hashtag

Much like how the @ sign is synonymous with direct communication, like emails and @mentions within social networks, the #hashtag symbolises open communication. Like many others, I too fought for a long time with the concept of hashtagging within social media. There was no real clarity to its use unless you were a teenager, it seemed. Just another method of meme-ing with its #YOLO and its #SWAG and #whatever. But beyond the facade of trendy tags, there’s a whole world of communities based around a single hashtag. Group discussions with people who actually have real things in common, whether that’s a hobby or a name or even a town of residence. Hashtagging is not just for teenagers, it has actually proven to be an effective form of communication for a variety of different people. It’s also a good way of grouping messages about certain events or even brands for easier information search. Nearly all social networks have now incorporated the use of hashtags into their messaging system. Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Tumblr, Flickr, Pinterest and many more. All the big players. It’s almost like, if you don’t hashtag, you’re a loser.

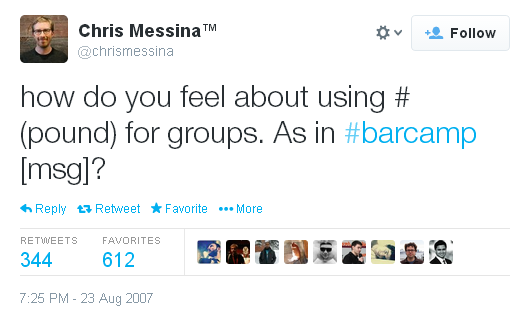

Though microblogging sites such as Twitter popularised the hashtag over recent years, the history of its internet existence predates the social media phenomenon as we now know it today. Twitter is often seen to be the birthplace of the hashtag, and though it’s certainly where the modern usage of the symbol is derived from, the hashtag was used on the internet in a similar fashion years before Twitter.

Steve Boyd, self-proclaimed web anthropologist and futurist, was the first to coin the term ‘hashtag’ for Twitter. Since then, the symbol has taken the world by storm, being officially entered into the Oxford English Dictionary and even being voted word of the year in 2012 by the American Dialect Society. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word ‘hashtag’ as meaning: a word or phrase preceded by a hash sign (#), used on social media sites such as Twitter to identify messages on a specific topic.

IRC (Internet Relay Chat) was created in 1988 and was a popular form of online communication during the toddler years of the internet. In IRC, you have to prefix the names of channels (chat rooms) with a # symbol. IRC users will often join multiple channels each serving a different community, and chat freely with other users on the server following the theme of whatever channel they were in at the time. IRC logs from 1991, during a Soviet coup d’état attempt media blackout, show users messaging incoming updates of the event in IRC channels like #NEWS. Two decades later and the parallels between this use of hashtagging and the more recent Egyptian revolution of 2011 is clear. The top hashtag of 2011 was not the tween flavour of the year but #Egypt, as millions flocked to Twitter during the Egyptian uprising to share or read the latest news in real time – posted with the hashtag #Egypt. Social media reduces the chance of bias that we could be getting if we were to rely on a single source for information. It offers the opportunity for everyone to present their perspective in an open forum. If it wasn’t for social media, we wouldn’t have access to 24/7 livestreams of the recent riots in Ukraine. Even the news has become social.

The idea behind hashtags is that they’re searchable and, if you see one that interests you, you click on it to be taken to every message with that hashtag inserted. It’s a way of content filtering. Even in IRC, someone mentions #otherchannel in the chat and you can usually click on it to be taken to that channel. And, like what has happened with hashtags on Twitter and Instagram nowadays, people also use this method of channel redirection in jest. For example: “Nobody likes you #GETOUT”. The joke being that the person then can click on #GETOUT and be taken to an empty room on their own (unless, of course, for whatever reason, the channel #GETOUT actually exists as a whole other community). The “hashtag” serves no searchable purpose, there’s no online chat community in #GETOUT, it’s just for humour.

As opposed to other forms of online groups where it may sometimes get rather elitist and “no, you can’t come in!”, anyone can join in with a hashtagged discussion on social networks. It’s easier to follow a discussion on Twitter by hashtag rather than by searching for generic keywords, and you can add to the discussion by including the hashtag in your own Tweet. You could even create your own hashtag and broadcast it to your followers. If they start participating in the discussion then their followers may catch wind of it and, should a hashtag become popular, the reach could be extraordinary.

How To Properly Use The #Hashtag

There’s a certain etiquette that even if you understand it, still gets some time to get used to. On sites like Twitter, overuse is seen as annoying and makes you look like a #noob. It even looks spammy and it’s become the social media equivalent of a keyword stuffed blog article. Whereas on image-based social media platforms like Instagram, it’s not uncommon to use multiple hashtags freely as it’s seen more as keyword-tagging your image and makes images easier to find. It’s almost like alt-tagging images in HTML; words can describe themselves but images need a helping hand in labeling the content. At least for now….

#AM #I #DOING #IT #RIGHT? One word: #NO.

It’s important no matter what social network you’re hashtagging on to keep the tags relevant to the context of your message. Stuffing trending hashtags into your irrelevant self-promotional Tweet makes you look like an idiot. You might get seen, but for all the wrong reasons. Even if you’re using them to convey a feeling or emotion like #yay or #noooo, it’s still within context of the message. Hashtags have developed to not only be intended for search but to add comical, informational or emotional value to the message. You can use hashtags to say you’re #sorry, to say you’re being #sarcastic, or even to announce to the world that you’re #pregnant. You don’t necessarily expect anyone to actually click through to join in a discussion about #sorry, the hashtag serves only to add additional commentary.

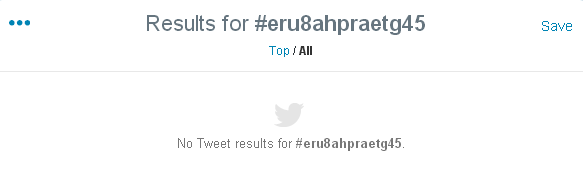

Creating hashtags is easy. I could smash my face down onto my keyboard right now and prefix it with a hashtag (#eru8ahpraetg45) and that’s all there is to it. People on Twitter will be able to click on it to see other Tweets that include that hashtag.

I’m not surprised.

Hashtags should be short, self-explanatory and catchy. Short to make the most out of micro-blogging platforms with character limits; self-explanatory because otherwise it’s like having to explain a joke to a person to the point it’s not funny – what’s the point?; and catchy because obviously you want it to catch on and spark a live discussion. Another popular mistake I often see people make is re-hashtagging the same word twice within one Tweet. You don’t need to prefix a word with the # symbol twice. For #example, I wouldn’t need to hashtag #example again, see?

Obviously, when constructing your hashtag, you can’t incorporate punctuation or spaces within the tag even to differentiate between words. Though thankfully, the tags aren’t caps sensitive so #hashtag and #HashTag both bring you to the same results. This makes how you capitalise your hashtag keywords rather significant. Susan Boyle’s promotional team learned this the hard way when they decided not to capitalise the first letter of each word for the celebratory hashtag Susan Album Party (#susanalbumparty – can you spot how this otherwise innocent hashtag could have been misinterpreted?) marking the release of her new album. By the time her PR team had noticed and deleted the Tweet, declining to comment on the mishap, the unfortunate hashtag had already gone viral and was beginning to trend worldwide. This led to days of first page ridicule, causing a devastating blow to her family-friendly image. Either that or it was a very good marketing ploy to drive some attention to her and her new album, no matter how crude the method.

#Hashtagging The Future

Social web services are transforming the way that we interact with online and offline media. From how we watch TV to how we listen to music. TV is no longer a spectator sport. We can actually participate with what’s happening on screen. Suggested hashtags flash up on screen mid-show so we know how to actively participate in the live online discussion about that particular scene in the TV show during that particular scene in the TV show. People don’t just sit down and watch TV as attentively as they used to; Ofcom reports from August 2013 show that 53% of Brits regularly watch TV whilst simultaneously using their mobile or tablet. With an astounding 11% admitting to discussing the TV shows online as they air. We don’t have to wait until the next morning at work or school anymore to talk about what happened on Eastenders last night; we just have to be online at the time.

Hashtags create buzz and I believe that they will continue to do so, especially as marketers firmly get to grips with the potentials of their uses. And as the internet becomes more and more social, hashtags will continue to grow in importance, building bridges between online communities.